A Closer Look at the “Inclusive” International Life at SNU

In recent years, Seoul National University has intensified its push toward globalization. From outbound exchange partnerships to short-term summer programs, SNU has focused its efforts on expanding into a more global university that attracts scholars from all around the world. Today, approximately 2,000 international students are enrolled, nearly 60% of them being full-time degree students—an indication that the university’s efforts are promising. However, as SNU looks outward, it must also assess how well it actually supports the international students already on campus. Although these students contribute to campus diversity, it appears that many feel disconnected from SNU’s global messaging in their everyday realities: welcomed but undersupported, trying to find their place in a community that is still figuring out how to include them.

Globalization vs. Everyday Reality

The feeling of disconnect begins from the moment international students browse and register for courses. Among the limited number offered in English, a majority fall under the general education category, and many of those focus on promoting Korean society and culture. For the most part, major classes are still conducted in Korean. Even in the Department of English Language and Literature, only about one-third of undergraduate courses over the last two years have been taught in English. The situation is more dire in the Department of Political Science and International Relations, where only around two to four courses each semester, across both undergraduate and graduate levels, are offered in English.

The challenge is not just in terms of the number of English-taught courses but also their inconsistent availability: what is offered, when it’s scheduled, and how frequently it’s taught in English. Even in departments such as Business Administration and STEM, which offer more courses in English, many international students have reported struggling.

One 2023 graduate from the College of Business Administration reflected that the courses conducted in English tended to be spread across diverse areas of study. As a result, without sufficient Korean proficiency, he could not delve deep into a singular subject. Moreover, many courses he wanted to take were either unavailable that year or taught in Korean, preventing him from creating a clear academic plan. Over time, this inconsistent offering leads to frustration and even a sense of inferiority as students struggle to keep up with classes and feel that they aren’t learning as much as they hope to.

The lack of English-taught courses is also a source of emotional fatigue. Even for international students with solid Korean proficiency, learning in another language poses a challenge. Mastering everyday conversational skills doesn’t translate to understanding complex academic terminology. When Korean terms don’t align with their English equivalents, students must undertake additional translation work before learning their course materials. The constant need to translate while keeping up with one’s studies is draining, making it more difficult to engage deeply with the academic content. Over time, this additional workload inevitably leads to mental exhaustion or burnout.

Overall, the lack of English-taught courses and their inconsistent distribution reflect a gap in SNU’s globalization efforts. Currently, it seems that the university’s reality doesn’t match up with the promoted inclusivity. Limited courses offered in English essentially limit students’ ability to fully engage with their studies, while the inconsistencies hinder them from taking part in a concrete academic track. For a university that aims to attract more international students, it’s ironic to see how students are invited, only to be left to navigate on their own.

Information Shortfalls and Ineffective Support Systems

Part of the reason why international students are surprised by the limited number of English-taught courses is the lack of transparency during the admission process. In the most recent International Admissions guideline, for example, applicants need only provide proof of competency in either English or Korean. Furthermore, the minimum level of Korean proficiency required by the application process is TOPIK 3, which is not enough for students to follow lectures or participate in Korean classes. As a result, many students enter SNU believing fluency in English is enough, only to later find themselves severely underprepared. While SNU does mention that students may need to take courses in Korean to fulfill graduation requirements, this information also appears only as a general advisory note in the FAQ. The expectation that students must be fluent in Korean to navigate academic life is never stated outright, causing incoming students to underestimate the language demands.

SNU has created various support systems in response to some of these challenges. Though well-intentioned, they still fall short in resolving the day-to-day struggles that international students encounter. The School-Life Mentoring Program (SMP), for instance, is a semester-long initiative that is meant to help international freshmen adjust to SNU and Korean culture. The program matches students with mentors based on their majors and interests, aiming to foster a sense of belonging. However, SMP fails to address the practical challenges that international students face, such as navigating administrative processes or figuring out how to access campus services. While activities like group studies, watching baseball, or having picnics can help students feel welcomed, they focus largely on socialization rather than offering tangible assistance.

More importantly, the effectiveness of the program largely depends on the level of engagement by mentors. Those who found the program helpful often reported having mentors who were invested, communicative, and active in reaching out to their mentees. For others, however, the experience was discouraging. Some mentors were too busy and treated the program as a formality. Others had good intentions but were unsure how to help. Existing language barriers also often contribute to miscommunication and awkward interactions. In my case, for instance, my mentor’s limited fluency in English combined with my own limited Korean made it difficult for me to express my concerns, and I was unsure how or what to ask for help.

SNU also provides academic support. Programs like the Academic Writing Program for international students, offered by the College of Humanities, aim to help students improve their Korean writing skills. The program offers both foundational lectures and practical classes where the instructor provides students with direct feedback on their work. These classes are primarily aimed at graduate students who are expected to write their theses in Korean. While it is well-intentioned, the program consists of only ten meetings total—five for each class type. Regardless of a student’s Korean proficiency, this limited timeframe is not enough to prepare one for the demands of graduate-level writing, leaving little opportunity for real improvement.

Invited, but Undersupported

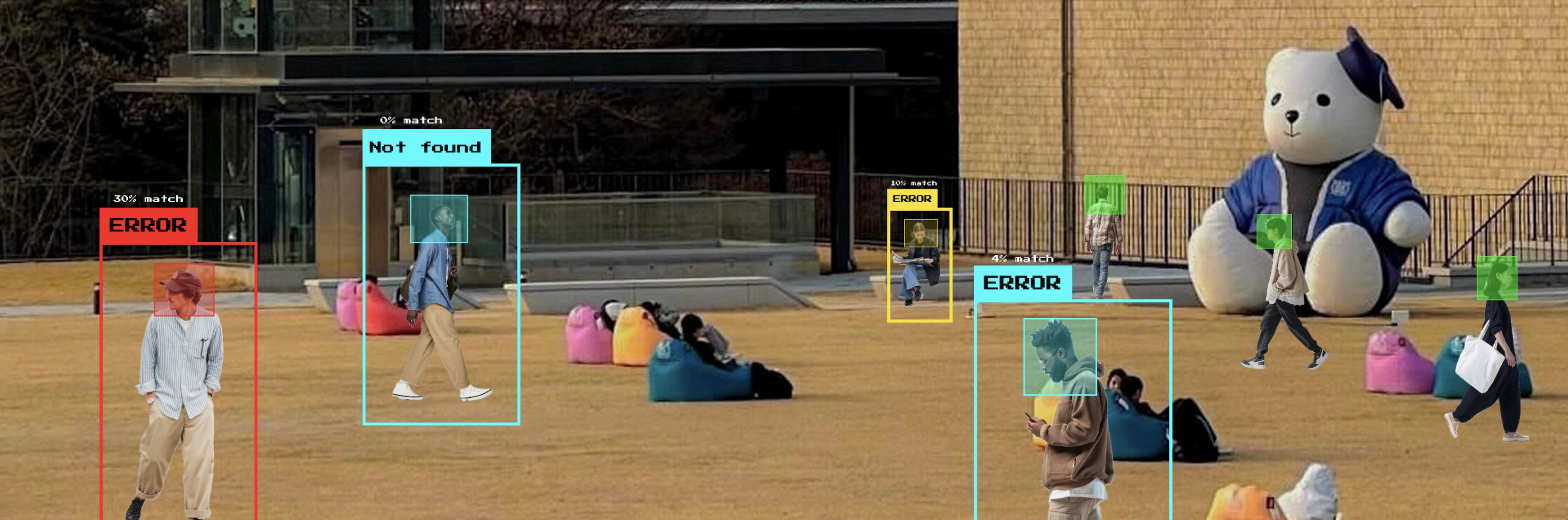

While navigating academic life may be difficult, the toughest challenge for many international students is adapting to the social and cultural environment. On paper, they are treated the same as domestic students, sharing classes and having access to major-based events. In practice, however, there aren’t any adequate programs designed to support their adjustment. Events like MTs, for example, are a common opportunity to build close relationships with fellow students early on. While they are technically open to everyone, the language barriers and cultural differences create an invisible wall that discourages participation. As a result, many miss out on the very experiences that could help them feel they truly belong.

In response, international students often take matters into their own hands. They actively join clubs and build meaningful bonds with both Korean and international peers over shared interests. They create their own sense of belonging, making the most out of their experiences. While these strategies are effective, they also highlight that the responsibility of integration is mostly placed on the students themselves. The support they receive from the university remains only superficial and poorly structured.

A Glimpse of Hope, but Work Remains

Amid these struggles, it would be unfair to frame the whole experience as negative. Many international students have managed to build a community and find comfort within SNU. Some speak of supportive friendships and kind, attentive professors, while others feel connected through small moments—like sharing frustration over difficult courses with fellow students. Moments like these, though subtle, offer much emotional relief.

There are also signs that things are improving. In recent years, organizations like the SNU International Student Association (SISA) or the International Student Organization (ISO), based in Gwanak Residence Hall, have begun hosting more events aimed at international students. Beyond traditional welcome parties or exam-season care packages, SISA now offers more opportunities for networking and cultural exchange. Their weekly coffee breaks or language exchange program creates spaces where students can meet and connect.

That said, these are still early steps. The core issues of institutional indifference and the everyday struggles of international students still need to be properly addressed.

Toward a More Inclusive SNU

Creating an internationalized campus is not an easy task, especially as Korea is a homogeneous country, and efforts to welcome and attract foreigners are a fairly recent development of the last twenty years. However, globalization is not merely about offering some English-taught courses and providing a few support programs. If SNU wants to be recognized as a truly global institution, it should put its message into practice through transparency in the admissions process and consistent academic and social support. What international students need is not just symbolic gestures, but real responses from the university to their everyday challenges.