Visible Space, Invisible Issues: A Report on Spatial Imbalance at SNU

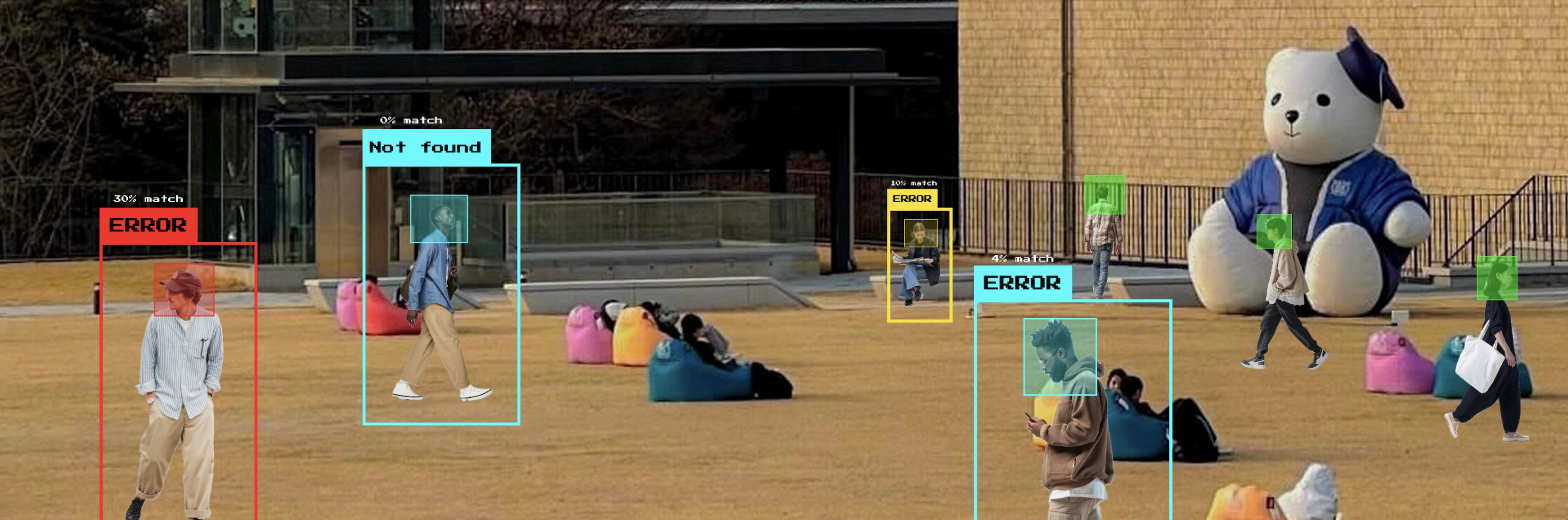

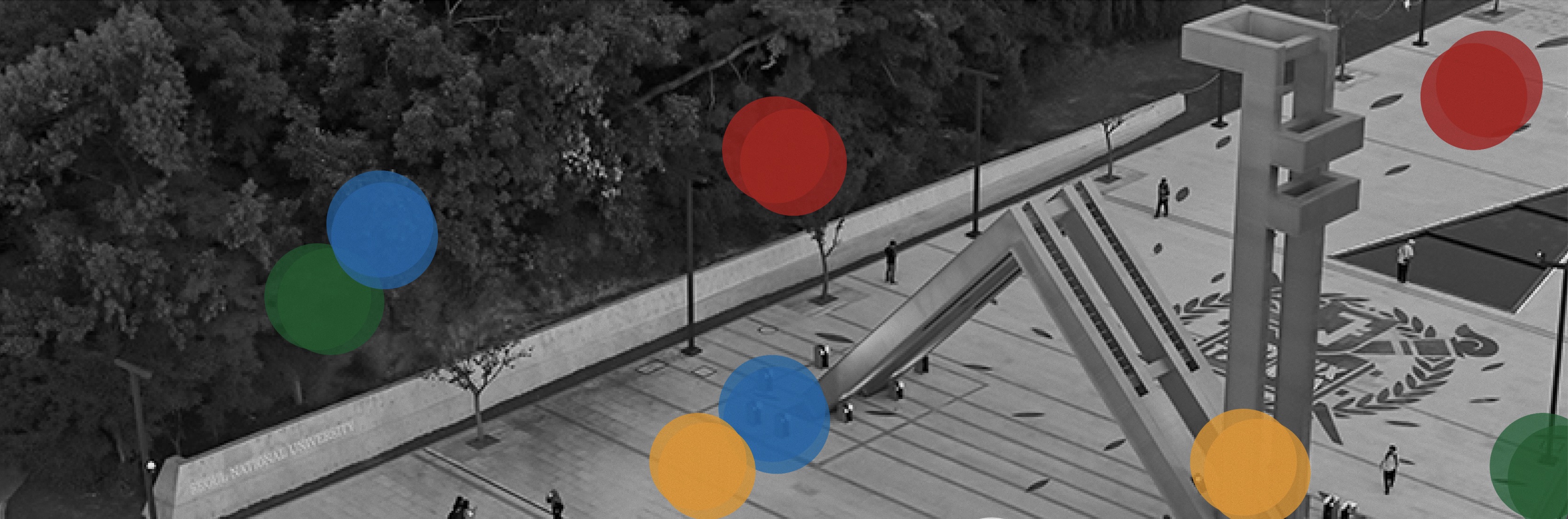

Every semester, Seoul National University’s Gwanak campus buzzes with students flooding out onto the walkways, crowding the buildings, and filling every sunlit bench. But while the campus grows livelier by the day, so too does a quiet, shared frustration—the struggle to find a space simply to be. In hallways, on-campus cafes, and empty classrooms, students quietly search for somewhere to study between lectures, take a break from campus life, or rehearse with their club. Group practices spill out onto outdoor spaces; naps are taken on benches; meetings are held in corridors. It’s not about poor planning on their part. Despite spanning over 4 million square meters and housing more than 200 buildings, SNU’s Gwanak campus holds a hidden problem: spatial imbalance. Issues arise because the university’s poor planning, mismanagement, and uneven resource allocation render much of the space unusable or inaccessible. But in a campus this big, no student should ever feel like there’s nowhere to go. The Paradox of PlentyAt first glance, SNU appears to have it all—majestic lecture halls, tree-lined walkways, and a campus so expansive it includes a pond and a lawn. The everyday student experience, however, tells a different, far less idyllic story. Many study lounges on campus are perpetually overcrowded. During exam season, finding an open seminar room or department-specific lounge can feel like winning the lottery. Students often hover waiting for someone to vacate their seat, and some end up studying on hallway floors or outdoor benches, regardless of the weather. Why is this the case?For one, the uneven availability of study rooms across departments is an issue. While well-funded colleges like Engineering have numerous dedicated lounges, certain colleges—namely the Social Sciences and Humanities—lack even the most basic facilities. In certain departments, students have no access to any quiet spaces aside from hallways. This falls short of meeting students’ needs, especially when they must remain on campus for extended periods between classes. One might ask, “Can’t students just go to the library to study?” They can, but it’s not always that simple. The Kwanjeong Library enforces strict silence, as even the slightest noise, like turning pages or coughing, can disturb and irritate others. While some prefer the silence, others find it stressful and unproductive for studying. The concept of nunchi (눈치)—the Korean term for the ability to read social cues—exacerbates this issue. In the library, any noise or breach of unspoken etiquette feels like a violation of nunchi. Another unofficial rule discourages sitting next to others, so as to ensure everyone has enough space to arrange their materials. As a result, many avoid available seats in order not to intrude, making the library feel full even when it’s only half occupied. Ultimately, students are left without flexible, multi-use spaces that accommodate diverse study needs. At SNU, department common rooms are also intended to be spaces where students can study, rest, or connect with peers between classes. In some fortunate departments, such as those in the College of Engineering or the newly founded School of Transdisciplinary Innovations, these lounges are well-equipped with sofas, microwaves, and communal tables, creating a welcoming environment. However, this isn’t the norm across campus. In older buildings, such as Building 58 of Business Administration or Building 16 of the Social Sciences, common rooms are often cramped, poorly lit, or missing entirely. Combined with poor management, space shortages are especially severe in departments with large student populations. Often, a single common room is expected to serve hundreds, resulting in overcrowding or limited access. Thus, students end up scattered across hallways or packed into cafes, blurring the line between rest and rush. In the College of Business Administration, over 500 students share just one common room. While each class is allotted a small table and a sofa, the space accommodates only about a dozen students—far from adequate. A sophomore by the name of Son expressed frustration, explaining that he often leaves campus between classes because there is simply nowhere comfortable to stay. The lack of adequate common areas leaves many students without a sense of belonging or a place to pause during the day. This shortage extends into the extracurricular sphere. SNU is home to hundreds of student clubs—from dance crews and theater troupes to sports teams and volunteer groups—but space for these organizations is also critically limited. The student union building operates at full capacity, forcing clubs to take turns using a small number of multipurpose rooms or claim whatever corner they can find. Department-registered clubs compete for remaining rooms, often receiving deteriorated spaces or nothing at all. Newer or unrecognized clubs face even greater challenges. Without designated rooms, students carry equipment in backpacks, rent expensive off-campus spaces, or meet in cafes. This inequality discourages emerging clubs and reinforces a hierarchy favoring established organizations over new, student-led initiatives. Overall, these structural and cultural constraints reveal a deep misalignment between campus infrastructure and the diverse needs of the student body. Without more inclusive and flexible spaces, many students are left navigating a campus that wasn’t fully designed with them in mind. Uneven Quality, Uneven AccessBeyond scarcity, there is also the matter of quality. While some spaces on campus have been renovated in recent years, others appear forgotten by time. Some club rooms have stained walls, faulty air conditioning, or broken furniture. Restrooms near older lounges often suffer from poor maintenance. And the lack of essential accessibility features in certain buildings renders them inaccessible to students with mobility challenges. This inconsistency in facilities and the need for renovation also applies to rest spaces. While a portion of colleges provide nap rooms or casual lounges, others leave students with no choice but to lie across desks or rows of chairs in empty classrooms. The disparity in comfort and cleanliness between buildings can be stark—and students notice. Moreover, many lecture rooms sit unused for hours, yet access is heavily restricted—often requiring prior approval or being reserved by departments regardless of actual need. Meanwhile, students are left studying onfloors or practicing outside. Adding to the frustration is a fragmented booking system. Some departments use outdated portals or paper sign-up sheets, while others have no system at all. This forces students to rely on personal connections or luck. Certain engineering students even use auto-booking macros to secure rooms instantly, creating an unfair advantage. In contrast to other universities’ live maps and smart systems, SNU’s approach feels outdated and unfair. For a school that champions leadership and innovation, this spatial imbalance creates a daily contradiction between what students are told they can do and what the campus actually allows them to do. Hidden Spaces, Untapped PotentialDespite these daily frustrations, solutions may already exist within the campus itself—if only administrators were to look more carefully. Beyond the lecture halls and seminar rooms, SNU contains overlooked, underutilized, or simply unknown places that could become vibrant student spaces with minimal investment. Located near the SHA gate and the College of Business Administration, the SNU Museum and the SNU Gallery offer spacious, climate-controlled interiors that are often underutilized. While these buildings are open to the public, they are rarely integrated into student life. These aesthetically inspiring spaces already contain quiet areas where students can rest while enjoying the arts. The venues can also be repurposed as places for student-led exhibitions and workshops hosted by clubs. By integrating these cultural spaces into student life, SNU can alleviate the demand for study and creative spaces, especially for students in the arts and humanities. Located next to the tennis courts and Daelim International House (Building 137-2), the Power Plant is another one of SNU’s most overlooked buildings. Once a utility facility, it now offers a large, open interior with high ceilings—ideal for club rehearsals, music practices, or performance art. With modest renovations, it has already hosted exhibitions and even a roller-skating rink. Further repurposing could ease demand for overcrowded practice spaces like the student union and transform this underused corner of campus into a vibrant hub of student creativity. Last but not least, the SNU Observatory and SNU Bungalow (Buildings 107-1 through 107-3), located on the outskirts of Gwanak campus, are little known to most students. These secluded locations could be designated for mindful relaxation, quiet reading, or nature-based wellness programs. SNU should take advantage of its natural habitat. With basic signage, maintenance, and awareness campaigns, the university could better integrate these natural settings into student life—something especially important in a high-pressure academic environment. A Campus Meant for Belonging From overcrowded lounges and locked seminar rooms to outdated infrastructure and opaque booking systems, students compete daily for essential spaces to study, rest, or create. The issue is deeper than mere logistics—it creates a culture where students feel like outsiders on their own campus. Inequitable space allocation, inadequate support for clubs and enforced silence in libraries further discourage collaboration and community. Without action, the heart of student life—connection, creativity, and comfort—continues to be pushed to the margins. SNU is not lacking in square meters—it lacks vision. Across the campus lie overlooked gems. If reimagined and made accessible, these spaces could dramatically transform the student experience from one of scarcity to one of possibility. The truth is simple: SNU has the space—it simply needs commitment. With modest investment, student input, and a dedication to equity, the university can unlock the potential already embedded in its architecture and landscape. It is time for SNU to view its space not merely as property, but as community: something to be shared, nurtured, and made truly livable. There is room to improve. More importantly, there is room to begin—right now.